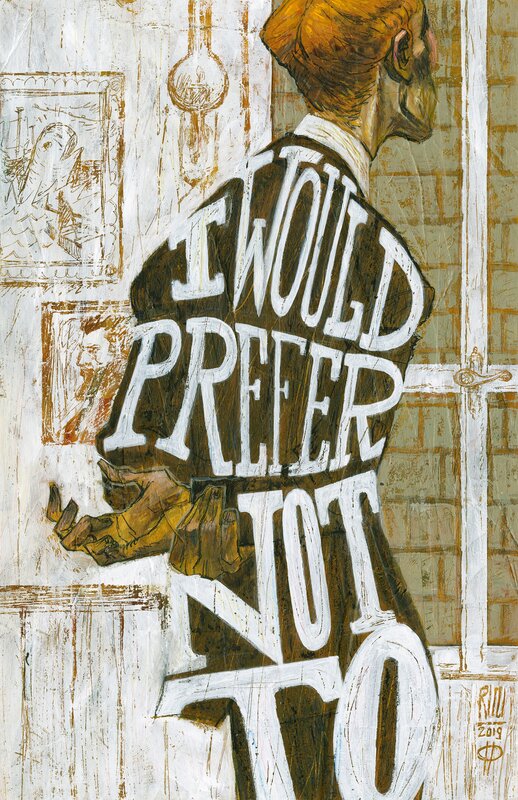

Both stories do indeed aim to make more visible the suffering of two groups of people in classically liberal societies: in "Bartleby," employees in certain kinds of labor markets, who bear the brunt of the pain of alienating and commodifying the products of labor, and in "Jury of Her Peers," wives in traditional, patriarchal marriages, who bear the weight of the institutionalized loneliness, abuse and injustice that such marriages often entail. Thus, legitimation, as well as the invisible pains that are legitimated, is the subject matter of both stories. I will argue that two short novellas, Herman Melville's "Bardeby the Scrivener" - which Thomas does discuss and Susan Glaspell's "A Jury of Her Peers" - which he does not - not only seek to articulate and give voice to the victims of such legitimated harms in the way Thomas suggests, but that they also quite directly concern the process of legitimation itself.

In this article, I hope to take this Thomasian claim one step further. Particularly from a perspective internal to the legal system, such harms can be extremely hard to discern. These harms tend, not coincidentally, to be the byproduct of institutions, social systems, and structures of belief which overwhelming serve the interests of powerful individuals, groups or subcommunities.Īlthough law does not cause these harms it is complicit in the process by which they become "legitimate" - an accepted part of the terrain of daily living - and hence become invisible, often even to the individuals who sustain them. As a number of critical legal scholars have argued, some of the sufferings of daily life - some of the harms individually sustained - are not simply not compensated by our positive law, but their very existence is aggressively denied, trivialized, disguised or legitimated by our legal rhetoric. There is, however, another type of suffering - another "category" of harms - toward which the law stands in a quite different relationship.

Still others are also concededly injurious, but nevertheless not cognizable because they were not in fact caused by a culpable individual. Other pains, although concededly injurious, and even concededly "caused" by some blameworthy individual or entity, are not cognizable. Somehow, by some process, some of the pains and suffering we sustain in life become cognizable legal injuries: if we are hurt through the defamatory utterances of others, we might seek compensation if we suffer a whiplash in an automobile accident when we're rear-ended on the road, we might seek compensation for the pain we're put in if we lose profits we might have made but for the interference of some third party with a contract we've entered, we might recover that loss.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)